What Additional Scale Relevant Policies Are Required?

Strengthening Existing Treaties

There are many positive components of the existing treaties dealing with biodiversity, and strengthening these treaties could improve protection of biodiversity. Some of the most important improvements to consider are:

-

Highlighting and dealing with the inherent contradiction between economic growth and biodiversity preservation, and giving preference to biodiversity protection

-

Obtaining support of all nations

-

Strengthening the legislative force behind each treaty

-

Strengthening the monitoring and enforcement mechanisms

-

Clarifying the supremacy of these treaties when conflicts emerge with the WTO

-

Support for scientific understanding of ecosystem services and their dependence on various forms of biodiversity

International treaties are entered into by national governments. The overwhelming majority of national governments places a priority on economic development, and generally protects that priority in any international agreements which they negotiate. By design, international treaties do everything possible to avoid compromising this priority, even if this means weakening the overall purpose of the treaty.

Optimal Scale for Biodiversity

Optimal scale is that level of sustainable throughput which provides the greatest ecological and social benefits (see Optimal Scale in Sustainable Scale). As such, it is the primary policy objective of sustainable scale.

In the case of biodiversity protection, optimal scale has to do with reducing the sum total of human activities that are collectively destroying critical biodiversity across the planet. It involves acknowledging that the physical size of our current economic activities is incompatible with maintaining life supporting ecosystems.

“Sustainable development” is an explicit goal of the biodiversity treaties. However, these treaties are not clear regarding the inherent conflict between continuous economic growth beyond the point of providing net benefits, and preserving biodiversity. Adhering to the dominant notion that continuous economic growth is in itself a desirable goal, and that only minor adjustments are needed to make it sustainable, avoids the inevitable acceptance of biophysical limits.

Optimal scale accepts these limits and strives to identify the point at which economic activities maintains critical life support ecosystem functions (i.e. is within sustainable scale), as well as produces more benefits than costs (from ecological and social, as well as economic perspectives).

While identifying optimal scale is a key objective from a sustainable scale perspective, it is a tall order as there are at least two major hurdles to identifying optimal scale for biodiversity:

-

There are a wide range of human activities that threaten biodiversity, including expansion of cities, roads and other transportation systems, industrial agriculture and monocropping, mining and logging operations, fishery practices, emissions of various toxins and other substances from a wide variety of industrial processes, and so on. There is no single activity that can be adjusted or eliminated to reduce biodiversity loss. Rather it is the sum total of these activities that must be reduced to preserve biodiversity (as evidenced by the global ecological footprint data, for example, see A Sustainable Scale Perspective)

- Our relative ignorance of the full extent of biodiversity’s contribution to global life support systems. This is a complex issue involving the relative lack of scientific information about the life supports obtained from biodiversity, and how biodiversity interacts with the non-living components of the earth. In addition, there is also the psychological and spiritual value we derive from biodiversity, and the ethical issue of respect for all life, regardless of its specific value to humans.

Dealing with Multiple Causes of Biodiversity Loss: “It’s the Economy, Stupid”!

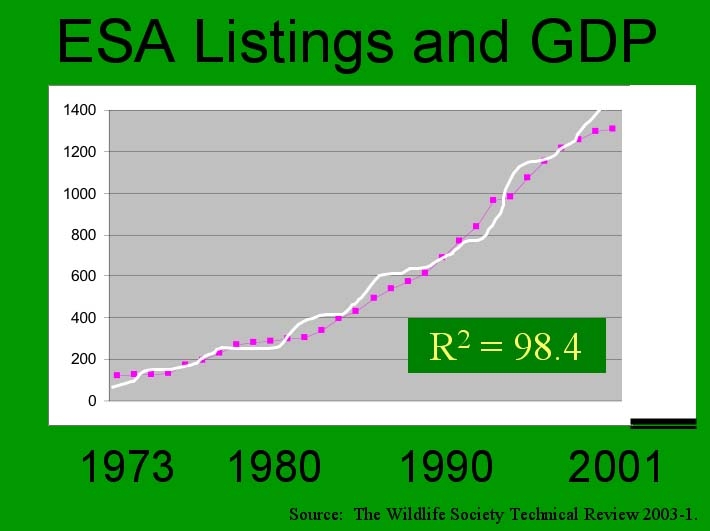

The list of specific causes of  biodiversity loss is very long (see above Scale Problem). In addition to specific changes in each of these areas of economic activity to make them more ecologically sustainable (see Sustainable Business Practices), there is also a need to rethink the role of economic growth itself. This is true for all Areas of Concern, but particularly pertinent for biodiversity loss.

biodiversity loss is very long (see above Scale Problem). In addition to specific changes in each of these areas of economic activity to make them more ecologically sustainable (see Sustainable Business Practices), there is also a need to rethink the role of economic growth itself. This is true for all Areas of Concern, but particularly pertinent for biodiversity loss.

The facts show that human well being does not require the high level of growth which currently characterizes the global economy (see Understanding Human Happiness and Well Being). To be sure, the poor in developing countries require more material goods for a sufficient livelihood.

Bbut many, and especially developed, nations waste enormous amounts of energy and materials in economic activities that add little if anything to human well being and happiness (see Understanding Human Happiness and Well Being; and A Hopeful Note? in Energy: Scale Problem).

Biodiversity protection requires a reduction in global economic growth, especially growth in developed nations. As long as national governments continue to support corporate interests for more economic growth rather than to achieve ecological sustainability and social justice, international treaties will, by design, remain weak and their implementation will be ineffectual.1

Appreciating Biodiversity

We are only beginning to understand both the science of biodiversity and the psychological and spiritual role that biodiversity plays in human well being. Greater understanding of both these dimensions is essential to clearly articulating optimal scale. A variety of major scientific investigations are underway to better understand the science of biodiversity and its role in ecological sustainability (Millenium Ecosystem Assessment).

Despite these significant efforts and the new knowledge they will provide, we should not anticipate that such studies will provide us with a complete picture of the interdependencies between human well being and biodiversity soon, if ever.

Likewise, the role of biodiversity and contact with nature in terms of human psychological and spiritual well being is just beginning to be explored, but there is some evidence that the connections are real and deep. Given the many global changes resulting from problems of sustainable scale (see Areas of Concern), it is highly likely that these connections will become even more important as the changes intensify and we seek a new understanding of our relationship with the natural world we are part of.

A Precautionary Approach to Biodiversity Loss

There are many specific aspects of biodiversity’s importance to human survival and well being that we do not yet understand. However, there is no doubt about the fundamental fact of our dependency on this biodiversity, and lack of full information should not be a deterrent to stronger actions to protect biodiversity. The current rate of species loss should be taken as the canary in the mine whose death signals invisible danger.

The precautionary principle is an explicit part of the Convention on Biological Diversity, but it is more often than not ignored in favor of economic development. This misplaced emphasis might be forgiven if the economic development was targeting the world’s poor, but more often than not it is producing goods and services for those who already have abundance.

Strengthening the role of the precautionary principle is an essential step in reducing biodiversity loss. Where conflicts exist between biodiversity protection and economic growth, arguments of economic necessity should have to meet a high standard of providing goods or services for the world’s poor, and meet the highest standards of sustainable business development (see Sustainable Business Practices).

Roles for Civil Society

As noted above, when national governments enter into international treaties they generally protect the priority of economic growth over all other considerations, including the stated goals of the treaty.

Greater involvement of civil society is needed to counter the undo influence of corporate interests on government priorities.

And considerably more public education is needed to inform people of the issues at stake and the range of options available. Such public engagement is essential for identifying many of the issues required to define optimal scale: what level of economic activity is sustainable? How is social justice to be effected, for both present and future generations? And what are our ethical obligations to other species? This last item is central not only to dealing with protection of biodiversity, but also in determining optimal scale for all Areas of Concern.

References

1Speth, James (ed.). World’s Apart: Globalization and the Environment. Washington: Island Press, 2003: p. 90-110.